Paleontologists have examined the 514-million-year-old specimens of Gangtoucunia aspera, a tube-building marine animal from the Guanshan Lagerstätte of Yunnan province, China. Their results appear in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

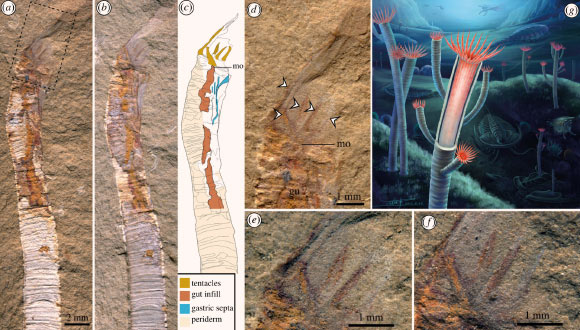

Specimen of Gangtoucunia aspera preserved in situ in a dwelling tube with soft tissues and life reconstruction: (a) overview of oralmost region of part, boxed region shown in (d); (b) overview of oralmost region of counterpart; (c) interpretative drawing combining information from both part and counterpart; (d) detail of oral region and tentacular apparatus of part; (e) close up of tentacles in part; (f) close up of tentacles in counterpart; (g) life reconstruction of Gangtoucunia aspera. Image credit: Xiaodong Wang / Zhang et al., doi: 10.1098/rspb.2022.1623.

“A tubicolous mode of life is common among animals, with the tubular exoskeleton providing a variety of functions including protection from predation, supporting and elevating the body during feeding, assisting in respiration in oxygen poor environments and isolating animals from hostile surrounding conditions,” University of Oxford researcher Luke Parry and colleagues wrote in their paper.

“Tubes are common among the oldest assemblages of skeletal fossils in the latest Ediacaran and Early Cambrian epochs, indicating the importance of this lifestyle during the assembly of the oldest animal-dominated communities.”

“Examples of early tube builders are known from across the animal tree of life, including cnidarians, annelids, hemichordates, lobopodians and scalidophorans as well as numerous examples with unknown or controversial phylogenetic affinities.”

In the study, the researchers examined four specimens of Gangtoucunia aspera with soft tissues still intact, including the gut and mouthparts.

They found that that this species had a mouth fringed with a ring of smooth, unbranched tentacles about 5 mm long. It’s likely that these were used to sting and capture prey, such as small arthropods.

The fossils also show that Gangtoucunia aspera had a blind-ended gut, partitioned into internal cavities, that filled the length of the tube.

These are features found today only in cnidarians (modern jellyfish, anemones and their close relatives), organisms whose soft parts are extremely rare in the fossil record.

The findings show that these simple animals was among the first to build the hard skeletons that make up much of the known fossil record.

Gangtoucunia aspera would have looked similar to modern scyphozoan jellyfish polyps, with a hard tubular structure anchored to the underlying substrate.

The tentacle mouth would have extended outside the tube, but could have been retracted inside the tube to avoid predators.

Unlike living jellyfish polyps however, the tube of Gangtoucunia aspera was made of calcium phosphate, a hard mineral that makes up our own teeth and bones. Use of this material to build skeletons has become more rare among animals over time.

“This really is a one-in-million discovery,” Dr. Parry said.

“These mysterious tubes are often found in groups of hundreds of individuals, but until now they have been regarded as ‘problematic’ fossils, because we had no way of classifying them.”

“Thanks to these extraordinary new specimens, a key piece of the evolutionary puzzle has been put firmly in place.”

The new specimens clearly demonstrate that Gangtoucunia aspera was not related to annelid worms as had been previously suggested for similar fossils.

It is now clear that the animal’s body had a smooth exterior and a gut partitioned longitudinally, whereas annelids have segmented bodies with transverse partitioning of the body.

“The first time I discovered the pink soft tissue on top of a tube of Gangtoucunia aspera, I was surprised and confused about what they were,” said Yunnan University Ph.D. student Guangxu Zhang.

“In the following month, I found three more specimens with soft tissue preservation, which was very exciting and made me rethink the affinity of Gangtoucunia aspera.”

“The soft tissue of Gangtoucunia aspera, particularly the tentacles, reveals that it is certainly not a priapulid-like worm as previous studies suggested, but more like a coral, and then I realized that it is a cnidarian.”

_____

Guangxu Zhang et al. 2022. Exceptional soft tissue preservation reveals a cnidarian affinity for a Cambrian phosphatic tubicolous enigma. Proc. R. Soc. B 289 (1986): 20221623; doi: 10.1098/rspb.2022.1623